Surprising Serpents

Studies show which snakes strike fastest, including the monster Titanoboa

By Charlie Bier (La Louisiane Fall 2016/Winter 2017 p. 2-3 )

University researchers are shedding light on snakes and their behavior, from venom-injecting vipers to a prehistoric constrictor called Titanoboa, an almost 50-foot-long giant too thick to squeeze through a modern doorway.

In one case, research conducted by Dr. Brad Moon, an associate professor of biology; Dr. David Penning, a former UL Lafayette doctoral student; and Baxter Sawvel, a graduate student, took the fangs out of the widespread misconception that venomous snakes, such as rattlesnakes and cottonmouths, strike faster than nonvenomous snakes.

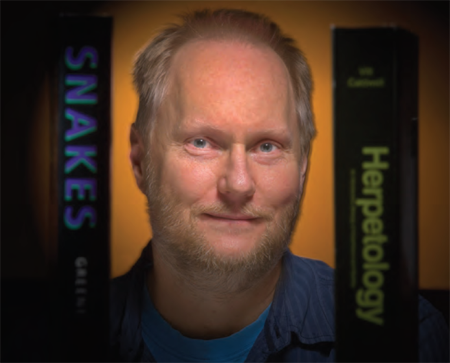

Dr. Brad Moon photo by Doug Dugas

Dr. David Penning photo by Doug Dugas

The three researchers published an article in "Biology Letters," a scientific journal based in London. "Debunking the Viper's Strike: Harmless Snakes Kill a Common Assumption," challenges a longstanding belief that vipers possess the quickest strikes of all snakes.

The discovery came, in part, by chance. The researchers were conducting a study to determine how the size of snakes affects strike speed. In the process, they came to an astounding realization. While measuring defensive strike capabilities of Texas rat snakes, they noted that the nonvenomous snakes struck with acceleration and velocity that rival western diamondbacked rattlesnakes and western cottonmouths, also known as water moccasins. The revelation, shown in slow-motion playback of high-speed videos, was so surprising, the researchers couldn't believe their eyes. So, they conducted multiple tests.

The scientists measured strike speeds of 14 Texas rat snakes, 12 western diamondbacked rattlesnakes, and six water moccasins locked in specially modified aquariums. Padded gloves attached to the end of long, wooden dowels were waved before the snakes. The rat snakes repeatedly struck as fast as, and in some instances faster, than vipers. "It was surprising initially, but when we thought about what we were seeing, it made sense, given that different kinds of snakes catch and eat similar kinds of foods. They have to catch the same kinds of rodents, and they all have to do it quickly," said Moon, a respected researcher and herpetologist who has studied a wide range of snake behavior and movements.

Research revealed that rattlesnakes struck fastest overall, at 28 Gs, which is force exerted due to acceleration or gravity. Rat snakes, though, were a close second, at 27 Gs. That's almost double the amount of G-force that could cause a fighter jet pilot to lose consciousness. For added perspective, vipers and rat snakes both hit their targets in about 50 to 90 milliseconds. In comparison, the blink of a human eye lasts about 200 milliseconds. "Basically, the primary conclusion is that vipers are not necessarily the snipers of the snake world. They strike quickly, but so do other snakes," said Penning, the paper's lead author.

That sort of reasoning resonated with dozens of international media outlets. National Geographic, The New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, and Discover, are just several that covered the findings.

While the discovery is intriguing, Penning said much work remains. With about 3,500 species of snakes in the world, "the question now becomes: How many other snakes can do this? We've tested three in a controlled setting."

Snake research conducted at the University also was included in a Public Broadcasting Service documentary that aired in November, although in a different context. An episode of the PBS series "Secrets of the Dead," titled Graveyard of the Giant Beasts, focused on which of two prehistoric reptiles might have been the apex predator in the rainforests of South America after a meteor strike wiped out dinosaurs more than 60 million years ago. The award-winning series relies on modern forensic methods and research to explore subjects like archaeology, disaster and disease, and historical figures.

An episode featuring Penning showed Titanoboa, an ancient 3-foot-wide snake estimated to have been 43-48 feet long and to have weighed 2,500 pounds. Titanoboa was pitted against the Cerrejon, a mammoth, 30-foot-long prehistoric crocodile with jaws as long as a person. Fossils of the two extinct reptiles were unearthed during coal mining operations in Colombia, South America. Titanoboa was discovered in 2009; it was thought to be the region's top predator, until the Cerrejon crocodile was discovered in 2012.

"Graveyard of the Giant Beasts" tapped experts to examine the behavior of today's largest snakes and crocodiles to try to determine which of the ancient reptiles might have been most dominant. A film crew visited campus and interviewed Penning, who has conducted a wealth of research about the striking and constriction capabilities of snakes, including some of the world's largest-pythons and boa constrictors. For the TV show, he relied on data he had collected over the past 3.5 years. Penning's objective was to try to determine something that had never been measured before: the potential strike speed and constriction power of Titanoboa. Penning worked in the laboratory, and visited zoos and private breeders, in his quest to gather information on large snakes, including a 15-foot long Burmese python.

A Tyrannosaurus Rex was about 40 feet long. A Titanoboa would have been five to 10 feet longer. (© 2016 THIRTEEN, Design By Victoria Malabrigo)

What Penning, who earned a doctorate in environmental and evolutionary biology in December 2016 and now teaches at Missouri Southern State University, learned was that Titanoboa could have struck at the crocodile in one- to two-tenths of a second. "Point two seconds is on the order of an eyeblink. So this is a very, very fast maneuver," Penning said. He also determined that the huge snake would have been able to crush prey with an overall constriction pressure of about 250 pounds per square inch, for a total of 1.3 million pounds of force. "I don't know of an animal that could deliver that kind of pressure today. For comparison's sake, we'd probably be talking industrial grade trash compactors or car crushers."